In recent years, the term xenophobic has gained attention, but the concept was already familiar to the Ancient Greeks, who grappled with the presence of foreigners in society.

While these words may sound unfamiliar to Western ears, they are rooted in the Greek words xenos (ξένος), meaning “foreigner” or “stranger,” and phobia, referring to a “fear” or “aversion.” The Ancient Greeks not only coined the concept but also developed social and cultural practices to address its implications.

Yet, paradoxically, they also valued its opposite: hospitality. The Greek virtue of philoxenia (φιλοξενία), which emphasizes generosity and kindness toward strangers, likewise originates with the Ancient Greeks. Researcher Gregory T. Papanikos, PhD, currently President of the Athens Institute for Education and Research, explores this duality in his article “Philoxenia and Xenophobia in Ancient Greece.”

Papanikos argues that Ancient Greek society was fundamentally shaped by a strong distinction between Greeks and “barbarians.” According to him, “Ancient Greeks were xenophobic rather than xenophiles,” though the intensity of these attitudes varied between city-states.

Xenophobic attitudes, the Greek identity, and “barbarians”

One of the clearest indicators of Ancient Greek xenophobia is found in the concept of the “barbarian.” Originally, the term barbaros simply described those who did not speak Greek and whose language sounded like “bar-bar” to Greek ears. Over time, however, it took on broader cultural implications, coming to signify people perceived as inferior or uncivilized.

Ancient literature frequently reinforced this distinction. The historian Herodotus, for example, described foreign customs as fundamentally alien to Greek norms: “Their customs are the very opposite of ours.” Such statements reveal a worldview rooted in cultural separation. Greek identity was defined by shared language, religion, and customs, while outsiders were often depicted as morally or politically inferior. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos emphasizes that this divide between Greeks and non-Greeks “shaped Ancient Greek identity and culture.”

It is important to note that Greek xenophobia was not primarily racial in the modern sense; it was cultural. The Ancient Greeks defined themselves not by ancestry but through paideia—their education, language, and civic engagement. Yet despite this focus on cultural markers over biology, the boundary between insiders and outsiders remained rigid and exclusionary.

Differences between city-states

Ancient Greece was not a unified nation but a patchwork of independent city-states, each with its own approach to foreigners. The two most prominent city-states, Athens and Sparta, exhibited notable “differences in the degree of xenophobic attitudes,” as Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos observes.

Sparta provides perhaps the clearest example of institutionalized xenophobia. Through the practice known as xenelasia (ξενηλασία), Spartan authorities could expel foreigners considered potentially harmful to the state. This policy reflected concerns that outsiders with different morals or loyalties might undermine Spartan discipline or act as spies. In Sparta, xenophobia functioned less as prejudice and more as a deliberate political and security strategy, aimed at preserving social cohesion and military strength.

Athens, in contrast, had a more nuanced approach. Often portrayed as open and cosmopolitan, the city prided itself on welcoming foreigners. In his Funeral Oration, recorded by Thucydides, Pericles describes Athens as “open to the world” and says the city-state would “never expel a foreigner.” Papanikos argues that this statement reflected confidence and cultural dominance rather than genuine hospitality. Athenians believed foreigners posed little threat because the city was powerful and culturally preeminent.

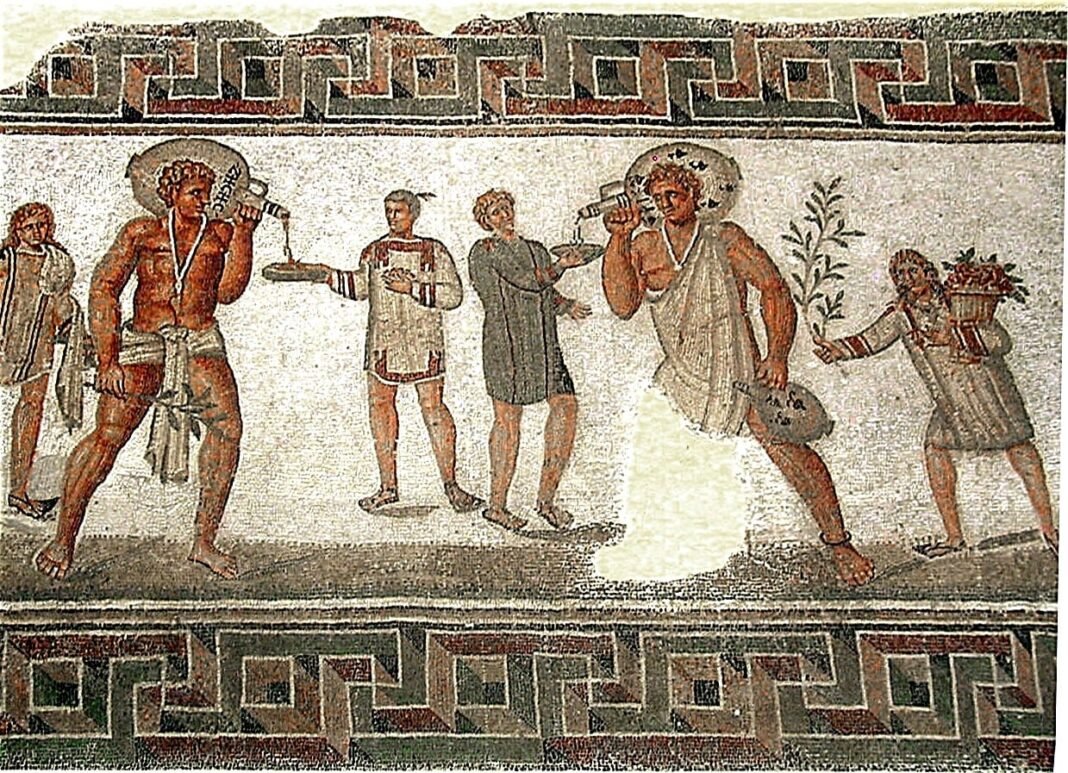

In reality, foreigners in Athens, known as metics (μέτοικοι), lived under legal and social restrictions. They had to register with authorities, pay special taxes, and were excluded from political rights. While Athens tolerated foreigners, it stopped short of fully integrating them into civic life, balancing openness with caution.

Ancient Greeks and philoxenia

Despite widespread evidence of xenophobia, Ancient Greek culture also celebrated philoxenia, or hospitality toward strangers. This concept was deeply embedded in both mythology and religion. In Greek myth, gods frequently appeared in disguise as travelers to test human kindness. Failing to offer proper hospitality could bring divine punishment, resulting in a moral incentive to treat guests well.

This produced a paradox: Greeks practiced hospitality not always out of genuine moral openness but often from fear of divine retribution or the expectation of reciprocity. Papanikos suggests that Greek hospitality was therefore conditional rather than universal. This duality—warmth toward guests coupled with suspicion of foreigners—lies at the core of Greek attitudes. Yet these behaviors were often practical rather than purely xenophobic.

Social and economic factors heavily influenced how Greeks treated outsiders. Because city-states were relatively small and resources limited, foreigners could be seen as competitors for land, trade, or political influence, heightening tensions. Foreigners were often perceived as economic rivals or potential threats, particularly during wartime. Additionally, Greek societies were highly stratified. Citizenship conferred significant privileges, and protecting these advantages frequently required excluding outsiders, reinforcing the practical, conditional nature of both hospitality and suspicion.

Representation of foreigners in literature and drama

A clear indicator of xenophobia among the Ancient Greeks can be found in their literature and drama, wherein foreigners were often depicted negatively. Tragedies such as Aeschylus’ Persians illustrate this tendency: non-Greeks are portrayed as emotional, irrational, and despotic, traits which contrast with the Greek ideals of rationality and freedom.

These portrayals reinforced cultural stereotypes and strengthened collective identity. Papanikos notes that such sources provide compelling evidence of widespread xenophobic attitudes in Ancient Greek thought and, by extension, behavior. Yet not all depictions were unfavorable. Some works acknowledged admirable qualities in foreign peoples, reflecting a more nuanced perspective and suggesting that Greek attitudes toward outsiders were not uniformly hostile.

Xenophobia, however, was not confined to foreigners; it also manifested among fellow Greeks. Rivalries between city-states fostered suspicion and hostility even among compatriots. Athenians, Spartans, Corinthians, and Thebans often viewed one another with distrust, sometimes engaging in open conflict. This intra-Greek tension highlights that xenophobia was rooted less in ethnicity and more in political and civic identity, reflecting concerns over loyalty, resources, and social cohesion rather than biological or racial differences.

Xenophobia and cultural exchange among Ancient Greeks

Despite their exclusionary tendencies, Ancient Greece was deeply connected to the wider Mediterranean world. Trade, colonization, and diplomacy enabled extensive cultural exchange, bringing new ideas, goods, and technologies into Greek society. Foreign artisans, merchants, and thinkers often played important roles, contributing significantly to economic, cultural, and intellectual life. Some foreigners even acquired citizenship through demonstrated loyalty and service, highlighting the practical flexibility within Greek society.

These examples demonstrate that Greek xenophobia coexisted with pragmatic openness. Greeks could simultaneously harbor suspicion of outsiders while depending on them for economic and cultural benefit. In this sense, the Ancient Greeks were indeed xenophobic but in a highly context-dependent and nuanced way. As Papanikos emphasizes, Greek society was fundamentally structured around a distinction between insiders and outsiders. Xenophobic attitudes appeared in language, law, and cultural representation, serving as a safeguard for civic identity and social stability.

At the same time, these attitudes coexisted with traditions of philoxenia, economic cooperation, and cultural exchange. Unlike modern racial ideologies, prejudice in Ancient Greece was primarily cultural and civic rather than biological. Greek perspectives on foreigners were shaped by practical concerns such as security, identity, and social cohesion rather than by irrational fear alone.