A new study suggests the Shroud of Turin — long believed by some to be Jesus’ burial cloth — was likely draped over a carved sculpture rather than a real human body.

The findings, published July 28 in the journal Archaeometry, come from Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian 3D designer known for reconstructing historical faces. Moraes used advanced modeling software to test how fabric behaves when placed over two different forms: a full three‑dimensional human body and a shallow, low‑relief sculpture.

The results pointed toward the sculpture. “Such a matrix could have been made of wood, stone, or metal and pigmented (or even heated) only in the areas of contact, producing the observed pattern,” Moraes said in an email.

Historic relic under question

The Shroud of Turin first entered historical records in the late 14th century. Almost immediately, debate erupted over whether it was a true relic from the crucifixion of Jesus.

In 1989, carbon dating placed the cloth’s origin between A.D. 1260 and 1390. The results strongly supported the idea that it was a medieval artifact rather than a burial cloth from the first century.

A new scientific study released today dates the Shroud of Turin to the time of Jesus. In His love, God is providing skeptics with information to believe before Jesus returns. pic.twitter.com/d7mgZcy4Ts

— Catholic Life (@prayandfast2) August 21, 2024

Art historians note that low‑relief religious images, such as carved tombstones, were common in Europe during the Middle Ages. This artistic tradition provides a plausible backdrop for how the shroud could have been created.

Digital simulations and the “mask effect”

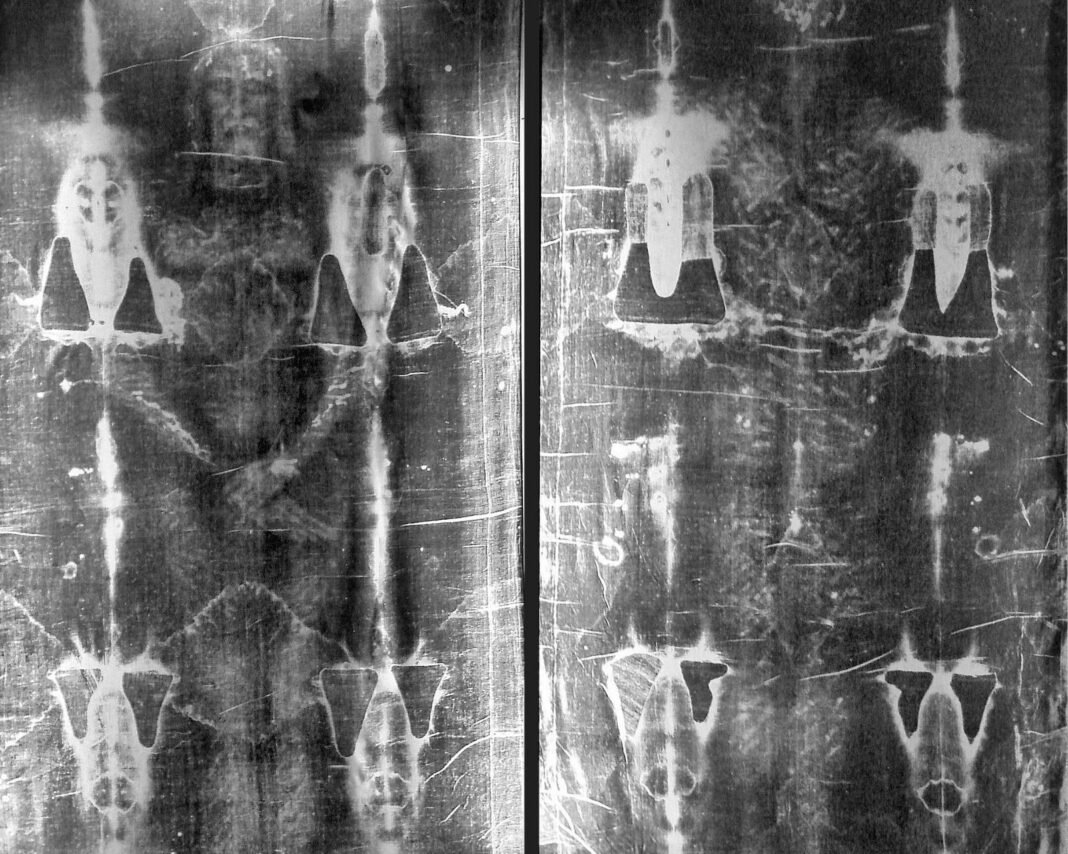

To test his theory, Moraes built two digital models — one a human body, the other a low‑relief figure. He then virtually draped cloth over both models and compared the results with photographs of the shroud taken in 1931.

The low‑relief model produced patterns nearly identical to the historic images. By contrast, the human body model distorted the features, stretching and widening them. Moraes referred to this distortion as the “Agamemnon Mask effect,” referencing the wide gold death mask excavated at Mycenae, Greece.

In a video demonstration, Moraes painted his face and pressed a paper towel against it. The resulting imprint appeared broader than his actual face, illustrating how a three‑dimensional object warps when transferred onto flat fabric.

Art or relic?

Moraes concludes the shroud is better understood as medieval funerary art. He called it “a masterpiece of Christian art,” while acknowledging a remote possibility that it could be an imprint from a real body. He believes skilled medieval artists or sculptors could have created the image using paint or low‑relief carving.

Andrea Nicolotti, a professor of Christian history at the University of Turin, agrees that the image aligns with low‑relief characteristics but says the finding is not new. In Skeptic, Nicolotti wrote that scholars have long recognized the shroud resembles a flat projection rather than an imprint of a human body.

Moraes argues his study adds value by offering a repeatable digital method to explore one of history’s most debated relics.