Climate change played a key role in shaping how ancient communities farmed and survived at the start of the Iron Age, according to a new study led by archaeologist Ebrar Sinmez. The research, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, examines how drought and cooling events thousands of years ago influenced farming choices and social stability in the ancient Near East.

Ancient droughts and farming choices

The team focused on two major climate shifts during the Holocene epoch: the 4.2 and 3.2 thousand years before present (BP) events. These episodes, marked by extended droughts and cooler conditions, left widespread marks on societies from the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean.

Sinmez and colleagues studied archaeobotanical remains from two sites in Turkey’s Amuq Valley: Tell Atchana, a political capital, and Toprakhisar Höyük, a rural center known for the production of olive oil and wine. Both were part of the same economic system, yet their responses to stress differed.

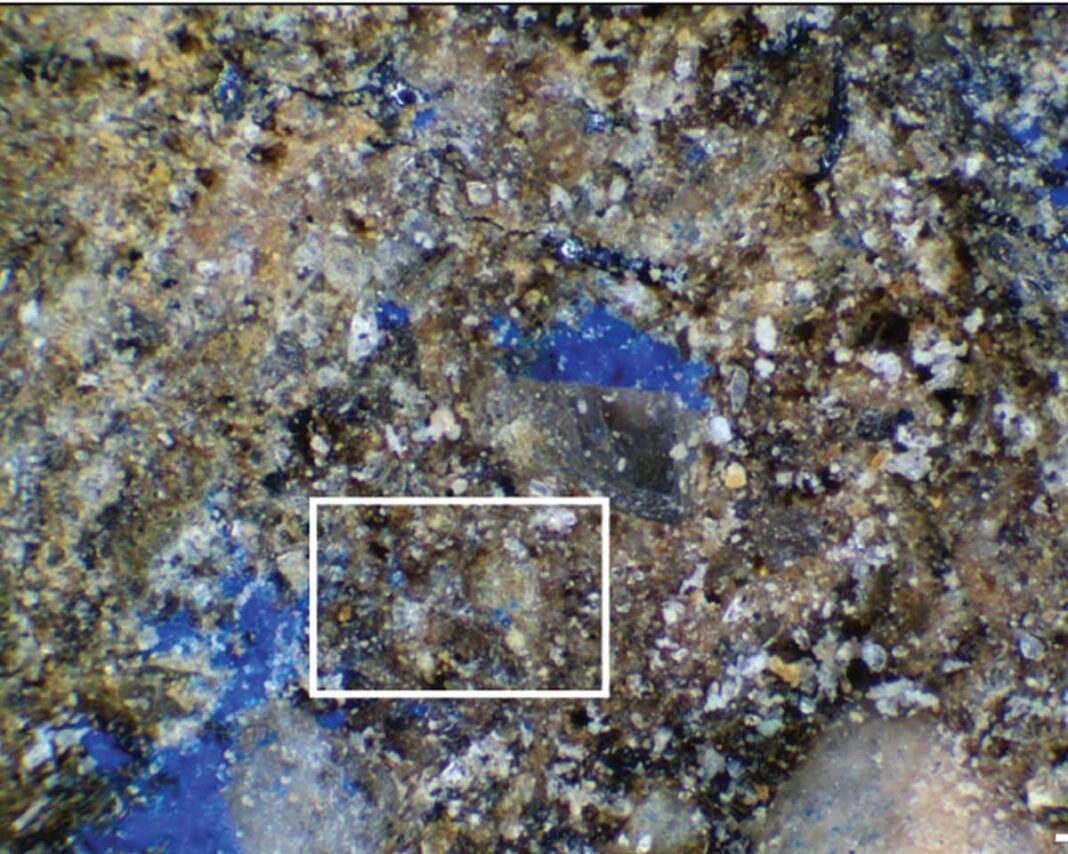

Wheat and barley, the staples of ancient agriculture, became indicators of change. Communities often turned to barley, which is more drought-resistant, when rainfall declined. Stable isotope analysis of cereal grains confirmed signals of water stress, revealing that climate instability left direct marks on crops.

Local effects, global echoes

The 4.2 ka BP event, beginning around 2200 BCE, lasted nearly 300 years. Scholars once described it as a “global megadrought,” tying it to the collapse of civilizations such as the Akkadian Empire and the decline of the Indus Valley cities. Yet Sinmez’s study stresses that the impacts were not uniform. While some regions faced a crisis, others adapted.

At Troy, for example, previous research has shown continuity despite reduced moisture levels. Western Anatolian communities responded by increasing barley and the use of goats, displaying resilience rather than collapse.

In the Amuq Valley, Tell Atchana may have relied on food imports and taxes to cushion its population, while Toprakhisar’s farmers had to adapt locally, possibly shifting crops and practices.

The second event, around 1200 BCE, marked a turbulent transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age. Drought and cooling struck again, coinciding with upheavals across the eastern Mediterranean. Ancient records describe a famine in Anatolia, grain shortages in the Levant, and the destruction of cities like Ugarit.

Societal stress and the Iron Age

Researchers argue the 3.2 ka BP event may have played a role in reshaping communities at the start of the Iron Age. In some areas, political powers like the Hittite Empire collapsed. There are written records that blame famine and grain dependence. Egyptian texts mention pleas for food shipments, while archaeological finds confirm that diets were shifting.

More than 3200 years ago, a vast, interconnected civilization thrived. Then it suddenly collapsed. What happened ?

Major civilizations of the Bronze Age at the time of its collapse include Egypt, Mycenaean Greece, Minoans, Hittite Empire, Assyria, Babylonia, and others. Many… pic.twitter.com/RwP3Sx03PB

— Archaeo – Histories (@archeohistories) April 10, 2024

In the Amuq Valley, Tell Atchana shrank and became more rural, while its neighbor Tell Tayinat rose as a new hub in the Iron Age. Sediment cores from the area show evidence of aridification, aligning with the broader climatic downturn.

Yet even amid disruption, some cities were able to recover. Sites like Tell Tweini in Syria show that urban life and farming resumed in the Iron Age after initial destruction.

A complex picture

The study underscores that climate alone cannot explain societal change. Resource overuse, shifting trade, and migration also shaped outcomes. Still, climate stress amplified existing pressures and often tipped fragile systems into crisis.

Sinmez points out that the comparison of urban and rural sites reveals how political power shaped resilience. Capitals could draw on taxation and imports, while smaller settlements had to experiment with new farming strategies. This layered response shows why some societies collapsed while others endured.

By tracing how ancient communities went through drought, famine, and recovery, the research highlights the fragile balance between the environment and human survival. It also provides a clearer picture of how climate shaped the course of history and how the Iron Age truly began.