Researchers have long worked to understand how Neanderthals moved from Europe to Asia during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic periods. This crucial chapter in Neanderthal migration marks their gradual disappearance and the rise of Homo sapiens as the dominant human species. A new study from Crimea now provides rare Neanderthal DNA evidence that helps trace that ancient journey.

Clues emerge from Starosele in Crimea

Starosele, an archaeological site on the Crimean Peninsula, has been considered an important location for Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals based on stone tools and other artifacts. But direct proof of their presence remained difficult to confirm. Bones at the site are often poorly preserved, making DNA testing nearly impossible.

Rare DNA discovery confirms Neanderthal presence

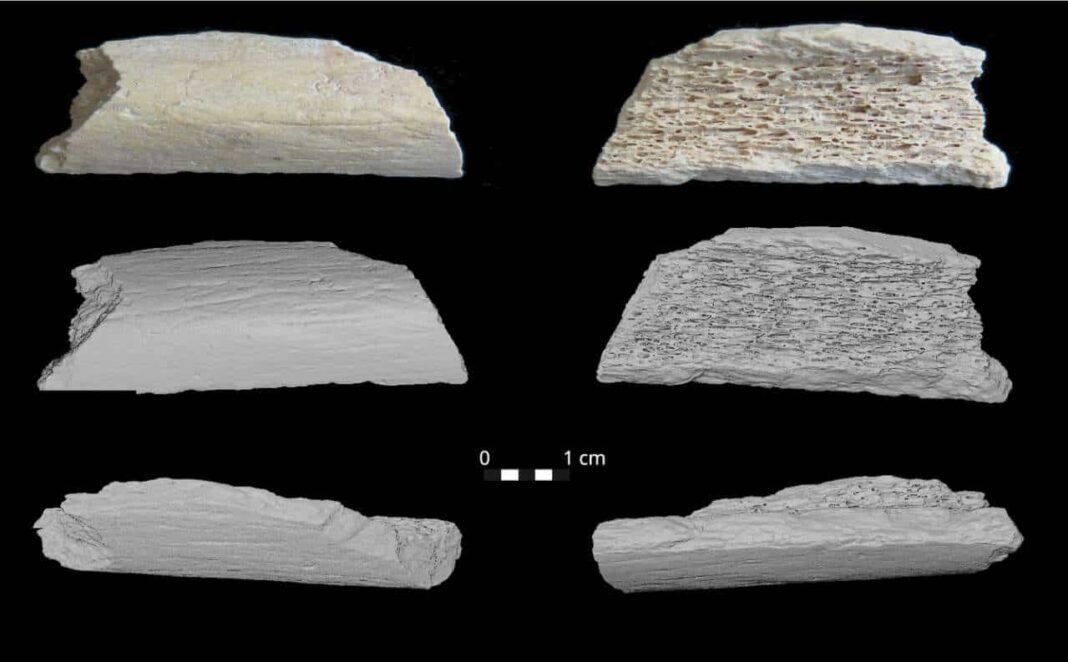

That changed when researchers examined 150 bone fragments recovered from Starosele. They identified DNA from a single Neanderthal using collagen peptide mass fingerprinting. The technique, known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS), helps classify tiny fragments when their physical features cannot. Radiocarbon dating placed the bone between 45,910 and 45,340 years old.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, marks the first confirmed Neanderthal DNA from the site.

Diet centered on horse hunting

Most of the animal remains uncovered belonged to horses. About 93% of the fragments came from them, suggesting that horses were a primary food source. Smaller amounts of bones from wolves, bison, and rhinoceroses were also found. These animals reflect the diverse Ice Age environment Neanderthals navigated for hunting and survival.

Genetic ties reveal a wider connection

The team then turned to mitochondrial DNA sequencing to learn more about the newly identified individual. Named “Star 1,” the Neanderthal showed genetic similarities to groups living farther east. According to the study authors, the findings support a connection between European Neanderthals and those in Asia, strengthening the idea of long-distance movement and interaction.

Stone tools from Starosele also match the style of artifacts discovered in the Altai region, a key area for understanding Neanderthal expansion. Researchers say this shared technology could reflect migration routes, knowledge exchange, or common cultural roots.

Ancient climate modeling suggests a migration pathway

To explore that possibility, the scientists ran habitat suitability models using ancient climate data. Their results identified a corridor along roughly 55° north latitude that would have provided favorable living conditions.

The route may have been open between 120,000 and 100,000 years ago, or possibly again around 60,000 years ago. The team believes this corridor could have supported travel and cultural exchange between the Crimean Peninsula and the Altai region.

A small fragment with a big impact

The bone fragment remains small and fragile, limiting how much information researchers can extract. But even as a single piece of evidence, “Star 1” brings Neanderthals in Crimea into sharper focus and adds an important clue to their final migrations before disappearing from the human story.