For centuries, scholars have pondered how the ancient Maya were able to predict eclipses with such remarkable accuracy. Now, a new study led by John Justeson has finally decoded those eclipse secrets, revealing that Maya predictions were based on a sophisticated system of lunar observations and calendar cycles.

The study, published in Science Advances, demonstrates that the Maya could accurately forecast solar eclipses centuries before modern astronomy emerged.

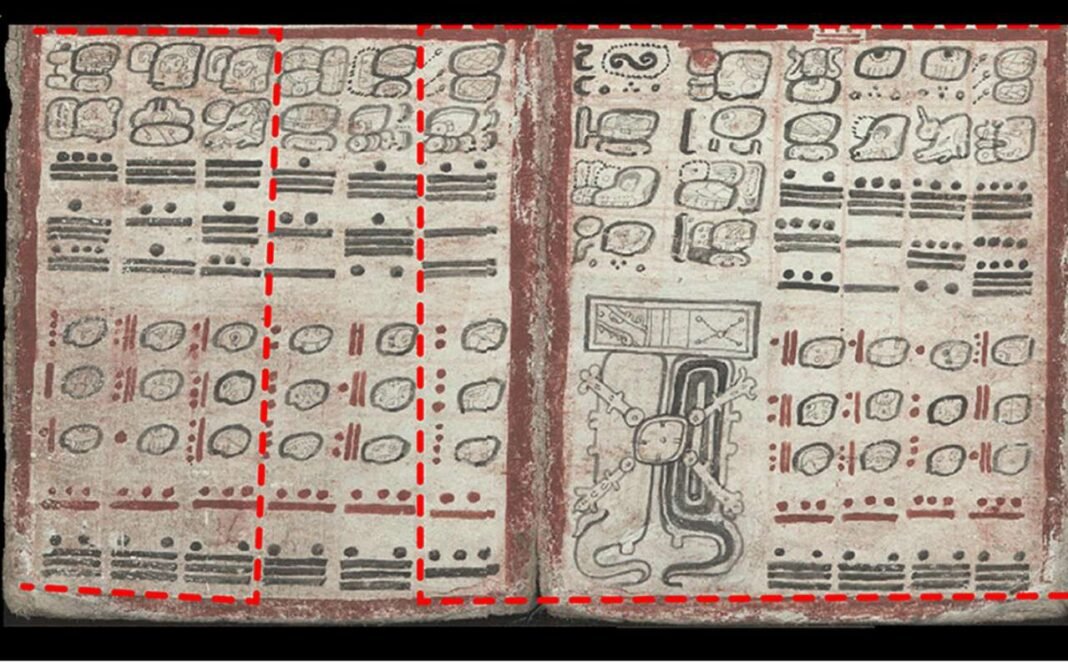

The key to the discovery lies in the Dresden Codex. It is one of only four surviving Maya manuscripts and is now preserved in a museum in Dresden, Germany. Written around the 11th or 12th century CE, it contains detailed tables tracking the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets—proof that the Maya were not only keen sky watchers but also brilliant mathematicians.

How the Maya predicted eclipses

Inside the Dresden Codex is an eclipse table, a series of symbols and numbers that once baffled researchers. Justeson’s analysis shows that the table was not just a list of past eclipses but a working tool for forecasting when the next one would occur.

Maya “daykeepers”—astronomer-priests who managed the calendars—used two main time cycles: a 260-day sacred calendar and a 365-day solar year.

By comparing the Moon’s phases to these cycles, they could pinpoint when the Sun and Moon would align and possibly darken the sky. They even adjusted their tables regularly to keep predictions accurate for generations.

Why this discovery matters

Justeson found that the Maya didn’t simply copy the same table over and over. Instead, they made small corrections every few decades, similar to how modern scientists fine-tune astronomical models. This kept their calculations precise for hundreds of years.

The Dresden Codex is one of the most important surviving Mayan manuscripts, created around the 11th or 12th Century AD. Although it originated in the Americas, it was rediscovered centuries later in Dresden, Germany, giving it the name by which it is known today. Today, this… pic.twitter.com/p9u3eS32Cj

— Dr. M.F. Khan (@Dr_TheHistories) October 8, 2025

What’s most remarkable is that this ancient knowledge wasn’t written in abstract numbers—it was built into the rhythm of the Maya calendar itself. The system connected the heavens to everyday life, guiding rituals, farming, and the timing of major events.

A civilization far ahead of its time

The study suggests that the Maya understood patterns in the Moon’s orbit well enough to predict solar eclipses visible across their territories, from Guatemala to Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. These events carried great symbolic meaning, often seen as signs from the gods.

By decoding this system, researchers now view the Dresden Codex not just as an artifact of faith, but as one of the earliest scientific tools in the Americas.

Bridging the gap between science and spirituality

For the Maya, astronomy and religion were inseparable. Every movement of the Sun or Moon carried divine meaning. Yet, behind that mysticism lay a mathematical precision that rivals that of later civilizations.

The new findings reveal that the Maya created a dynamic, self-correcting calendar that could track celestial events for centuries without telescopes or modern instruments.

A timeless achievement

The study reminds us that scientific curiosity is as old as civilization itself. Through their careful records and brilliant use of time, the Maya proved that understanding the cosmos wasn’t the privilege of modern science—it was already flourishing under the tropical skies of Mesoamerica a thousand years ago.