The assassination of Persian envoys in Macedonia is famously linked to Amyntas I, the first known king of the Greek kingdom of Macedon, in a remarkable story involving youths disguised as women.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (Histories 5.18–20) recounts the killing of the Persian diplomats in vivid detail. Although some modern scholars question the veracity of certain dramatic elements, the tale remains a valuable window into cross-cultural diplomacy, royal honor, and imperial pressures in the late 6th century BC.

Amyntas I (c. 540–498 BC) was the first recorded Macedonian king to form official connections with other states, including an alliance with Athens’ ruling Peisistratid family. At this time, Macedonia was a small kingdom on the northern edge of the vast Achaemenid Empire, ruled by Persian King Darius I.

To stay safe and maintain some independence, Amyntas recognized Persian overlordship, paying tribute and following certain demands while continuing to rule Macedonia. When Hippias, the former tyrant of Athens and member of the Greek Peisistratid family who had been expelled in 510 BC, came seeking support, Amyntas offered him the territory of Anthemus on the Thermaic Gulf, hoping to use Greek political rivalries to Macedonia’s advantage.

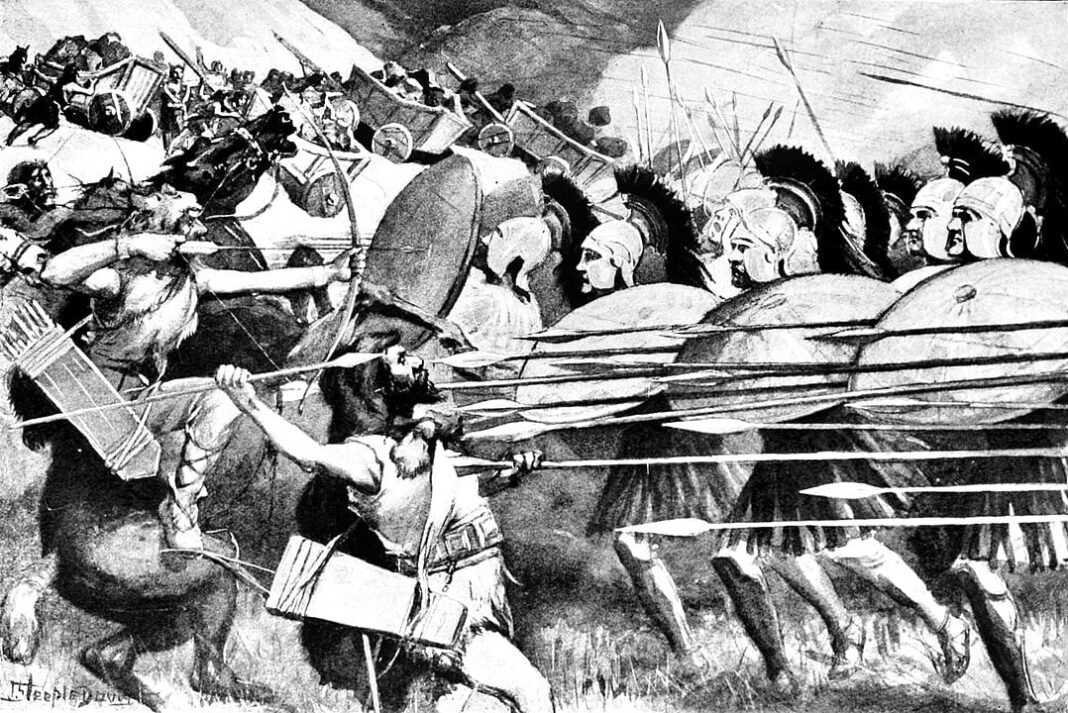

At the time, the small Greek kingdom of Macedon sat on the expanding frontier of the Achaemenid Empire. In this tense context, Herodotus narrated the episode in which King Amyntas I hosted a Persian delegation demanding “earth and water” for Darius the King—a symbolic token of Persian suzerainty—culminating in the controversial assassination of the envoys orchestrated under the watch of the young Macedonian prince, Alexander the I (also known as Alexander the Philhellene).

The Persian diplomats’ demands

When the Persian envoys arrived in Macedonia to demand absolute subjugation on behalf of King Darius I, Amyntas I acceded to the Persian ritual without resistance and welcomed them with a dinner of great splendor, exhibiting hospitality.

After the meal, the Persians pressed an additional cultural request—the presence of women in the symposium—which was foreign to Macedonian custom. Herodotus records them saying, “Macedonian guest-friend, it is the custom among us Persians, when we set forth a great dinner, then to bring in also our concubines and lawful wives to sit beside us.” Out of respect for his powerful guests, Amyntas reluctantly agreed despite the request being extravagant and culturally inappropriate.

Modern scholars have interpreted this scene in several ways: as a cultural anecdote contrasting Persian and Macedonian norms; as a pretext for escalating tensions; or as a narrative symbol of Macedonian submission mismanaged by elite insecurity. In any case, the exchange highlights the power imbalance between vulnerable Macedonia and the expansive Persian Empire.

Herodotus further recounted:

“Amyntas sent for the women; they came at call and sat across from the Persians. Then, seeing the women before them, the Persians complained that it made no sense; they said it would have been better if the women had never come than to sit opposite them and torment their eyes. Amyntas then bade the women sit beside them, and when they did, the Persians, flushed with wine, laid hands on the women and attempted to kiss them.”

The assassination of Persian envoys by the King of Macedonia

The young Macedonian Prince Alexander, later known as Alexander I, was outraged by the Persians’ behavior at the feast. Turning to his father, he said, “My father, you should rest and leave the drinking to me; I will handle our guests.” Amyntas trusted his son and departed.

Once his father had left, Alexander devised a clever ruse. He sent the women away “to wash” and told the Persians, “You may deal with these women as you wish, but for now, let them depart. When they return, you may continue.” Alexander then replaced the women with several beardless Macedonian youths disguised as women, each secretly carrying daggers. Once seated beside the Persian envoys, the youths attacked, killing all of them.

The Macedonians also eliminated the Persian servants and the rest of their entourage, burying the bodies and removing their carriages and belongings. When Persian troops came searching for the missing diplomats, Alexander ended the investigation by offering his sister Gygaea in marriage to the Persian general Bubares and paying a substantial bribe.

Herodotus wrote:

“This was the fate whereby they perished, they and all their retinue; for carriages too had come with them, and servants, and all the great train they had; the Macedonians made away with all that, as well as with all the envoys themselves. No long time afterwards the Persians made a great search for these men; but Alexander had cunning enough to put an end to it by the gift of a great sum and his own sister Gygaea to Bubares, a Persian, the general of those who sought for the slain men; by this gift he made an end of the search.”

Assassination of Persian envoys and sacred status

If Herodotus’ story is accurate, the killing of the Persian envoys in Macedonia would be an extraordinary case of assassination against diplomatic figures whose safety was normally considered sacrosanct even during times of hostility. This is why many modern historians approach the episode with skepticism.

Some scholars believe Herodotus may have fabricated the story to highlight Alexander I’s cleverness or that he simply repeated tales he heard while visiting Macedonia. Others find the almost literary nature of the plot hard to believe, questioning whether a king would trust such a sensitive task to an inexperienced prince.

Historian Eugene Borza, an expert on Macedonia, argued that if the story of the Persian envoys’ assassination is discounted, “there is no longer any evidence that Macedonia was a vassal-state during Amyntas’ reign.” This interpretation significantly affects how scholars view Macedonian autonomy versus subordination under Persia.

On the other hand, Nicholas Hammond, another prominent scholar, maintains that Macedonia remained a loyal subject of Persia as part of the satrapy of Skydra until the Persian defeat at Plataea. Hammond’s perspective suggests that even if the assassination episode is partly legendary, the overall political subordination of Macedonia to Persia at the time is historically sound.

Did Herodotus dramatize the assassination of Persian envoys in Macedonia?

Some researchers suggest Herodotus may have shaped this story as part of his technique of historiê—not just recording events but highlighting moral and cultural contrasts. In this interpretation, the feast and the Persian envoys’ visit illustrate Greek values, such as respect for women and proper ceremonial behavior versus Persian excess or impropriety. The assassination of the envoys thus may serve as an object lesson rather than a strictly factual account. Herodotus’ reputation as the “Father of History” is often accompanied by critiques of his blending of anecdote and analysis.

There is also a symbolic reading of the envoys’ request to fraternize with women. Scholars interpret it as a metaphor for the intrusion of “barbarian” influence into Greek society—a challenge to normative Greek gender boundaries—and the violent response as a narrative reversal of that intrusion. In this light, the assassination becomes an ideological device, emphasizing Macedonian Greek cultural identity resisting Persian domination.

Ultimately, the episode involving Amyntas, the feast, and the reported assassination of Persian envoys in Macedonia—whether historical fact or literary construct—reveals much about how the Ancient Greeks understood diplomacy, honor, and cross-cultural encounters. The Persian demand for earth and water symbolized submission and could have set the stage for hostile interactions between Macedonia and the mighty Achaemenid Empire.

Alexander I’s succession to the throne

Following the death of his father, Alexander I became king of Macedon (498–454 BC). He earned the title Alexander the Philhellene for his strong support of the Greeks. Although Macedonia was still a vassal of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, it retained a significant degree of autonomy under his rule. Alexander acted as a representative of Persian Governor Mardonius during peace negotiations after the Persian defeat at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC.

Herodotus refers to Alexander as “hyparchos,” meaning “viceroy,” after Mardonius’ conquest of Macedonia. Despite this Persian connection, Alexander frequently provided supplies and intelligence to other Greek city-states. Before the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, he warned Aristides, the Athenian commander at Tempe, to retreat ahead of Xerxes’ forces and showed the Greeks an alternate route into Thessaly, helping them plan their attack.

After the Greek victory at Plataea, the retreating Persian army, commanded by Artabazus, was attacked by Alexander’s forces at the estuary of the Strymon River. Most of the 43,000 survivors were killed, and Alexander eventually restored Macedonian independence after the Persian Wars.

Alexander also claimed descent from the Argive Greeks and the hero Heracles. A court of Elean hellanodikai, the judges of the Olympic Games, confirmed his Greek lineage, allowing him to participate in the Games, a privilege reserved for Greeks, possibly as early as 504 BC. He modeled his court after Athens and became a patron of the poets Pindar and Bacchylides, both of whom dedicated poems to him, earning him the epithet “Philhellene” for his support of Greek culture and affairs.