Greek temples may owe their iconic form not to abstract design or pure religious symbolism, but to the practical realities of ancient seafaring. According to a new academic study, classical Greek temple architecture may represent a stone interpretation of upturned rowing ships, pulled ashore and reused as shelter before becoming a lasting architectural model.

A long-standing mystery in Greek architecture

The research, led by José M. Ciordia and published in Frontiers of Architectural Research, revisits one of the most debated questions in classical archaeology: where Greek temple architecture came from, and why it developed its distinctive form. Despite centuries of study, many features shared by Greek temples have resisted convincing explanation.

These include sculptural elements placed high above ground, where they are difficult to see, the heavy entablature that appears to serve no clear structural purpose, and the subtle curves found in many refined temples, including the Parthenon. These curves are usually described as optical corrections, though their necessity has long been questioned.

Seafaring as the starting point

The study begins with the realities of ancient Greek life at sea. Ships were central to trade, warfare, migration, and survival across the Aegean and beyond. To protect wooden hulls from decay and shipworms, sailors routinely hauled vessels onto land.

To prevent rainwater from collecting inside and to create shelter, they could turn ships upside down and prop them on posts or low walls, using the inverted hull as a roof beneath which people could gather.

Researchers suggest that once ships reached the end of their working lives, some may have been reused as permanent roofs for communal buildings. Over time, even when real ships were no longer employed in this way, their form may have been imitated symbolically, first in wood and later translated into stone.

Doric entablature seen through a naval lens

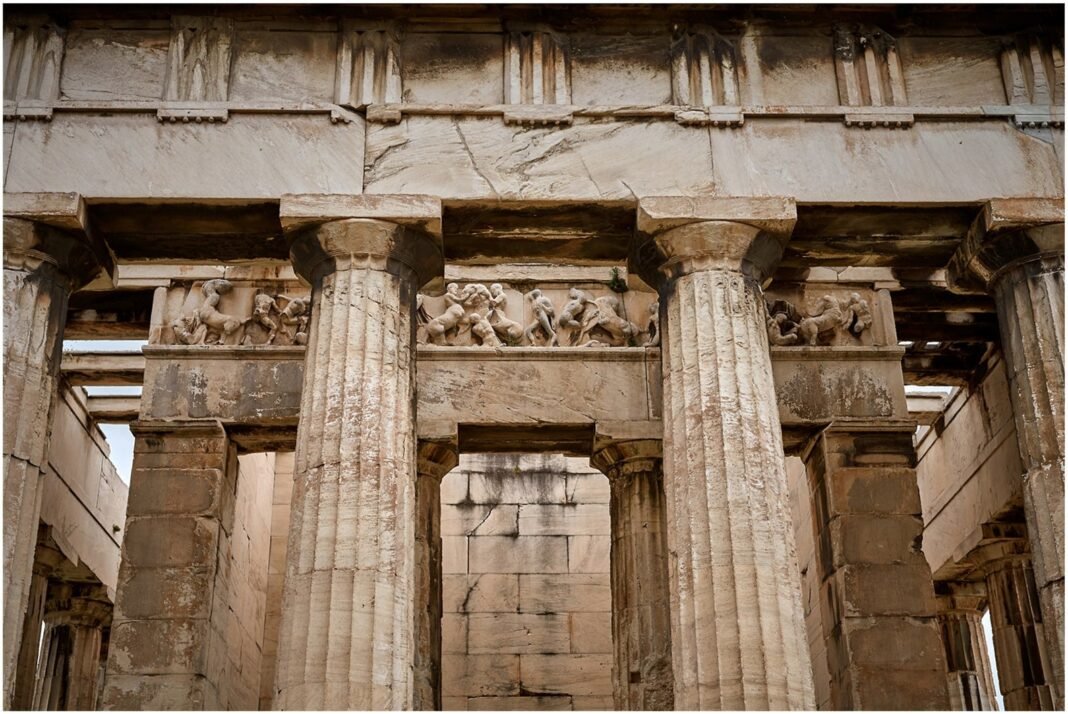

The clearest support for the theory appears in the Doric entablature, a defining feature shared by many early Greek temples. When the side of an ancient rowing galley is imagined upside down, its structure closely matches the elements of the Doric order. The ship’s upper screen aligns with the architrave. The rower openings correspond to the metopes. The vertical supports between them resemble triglyphs.

A new study suggests the Greek temple may be modeled on an upturned rowing ship pulled ashore by ancient seafarers. Researchers say this could explain the temple’s entablature, curves, and long-mysterious design features. pic.twitter.com/XVtvvUOTYJ

— Tom Marvolo Riddle (@tom_riddle2025) February 4, 2026

Even smaller details fit the comparison. Projecting blocks beneath the cornice resemble truncated supports once used to hold outriggers, the beams that kept oars away from the hull. Rather than abstract decoration, these elements may be stone representations of naval components preserved in architectural form.

Shields, curves, and hidden meaning

Other long-debated temple features also take on new meaning under this interpretation. Ancient ships often displayed shields along their sides. Greek historical sources describe shields hung high on temple entablatures, including on the Parthenon and at Delphi, a placement that closely mirrors naval practice rather than interior religious display.

The study also challenges the idea that temple curvature was purely visual. Wooden ships rely on gentle curves for strength and balance. Researchers argue that the slight curvature measured in temple roofs and entablatures across several sites may reflect ship design rather than optical illusion.

Ornament as memory, not decoration

Decorative patterns are reinterpreted in the same way. Rope-like carvings resemble hull reinforcement cords used on long, narrow galleys. Roof-edge ornaments shaped like waves resemble water pushed aside by a moving vessel.

Large ornaments at the peaks of temple roofs align with features associated with a ship’s prow, where spray is strongest. In this reading, architectural “ornament” becomes a form of cultural memory rather than embellishment.

Rethinking the surrounding colonnade

The theory also offers a new explanation for the peristasis, the ring of columns surrounding many Greek temples. Researchers suggest that, as earlier ship-based roofs deteriorated, builders added larger symbolic “ships” over existing structures.

Supporting these larger forms would have required perimeter columns, creating a surrounding colonnade that later became standard across temple architecture, even after its original structural purpose faded.

What the study does not claim

The research does not argue that stone temples were built from actual ship timbers. Instead, it proposes that Greek temple architecture preserves the form and memory of ships, not their physical remains. The ship survives as an architectural idea translated into stone.

No excavation has yet uncovered a Greek temple roof that can be proven to be a former ship. The authors acknowledge this limitation but stress that archaeology also relies on formal comparison, visual evidence, and historical context.

A new way to read the Greek temple

If the argument holds, it reshapes how Greek temples are understood. What has long been described as ornament may instead be representation. Greek temples emerge not as abstract inventions, but as monumental echoes of maritime life, preserving in stone the form of upturned rowing ships that once sheltered people along ancient shores.