Minoan Genii are mythological creatures that reflect the influence of Egyptian deities, offering a striking example of how Eastern Mediterranean civilizations interacted during the Bronze Age. When Ancient Greeks—and later the Romans—engaged with Egypt, this demonstrated that no civilization developed in isolation. Trade, diplomacy, and artistic exchange fostered a shared visual and religious vocabulary that crossed seas and cultures.

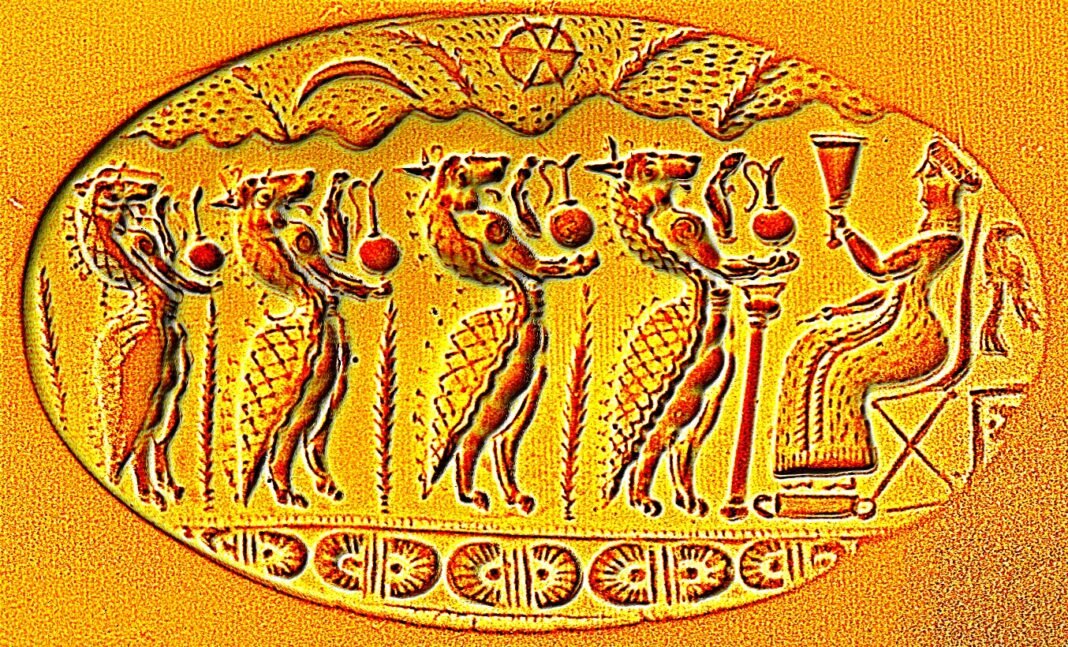

Artistic portrayals of Minoan Genii on Crete vividly illustrate this interaction. These Bronze Age mythological figures (2000–450 BC) blend human and animal traits and often appear in ritual contexts. Frequently depicted carrying vessels or performing ceremonial acts, they bear a notable resemblance to Egyptian deities, particularly the goddess Taweret and related protective spirits.

Taweret, the Egyptian goddess of fertility and childbirth, protected mothers and children. She had the head of a hippopotamus, pendulous female breasts, and a bloated, pregnant-looking stomach, as well as the limbs and paws of a lion and a crocodile-like tail. She also stood on two legs. This iconography was adapted in the Aegean during the Neopalatial period (ca. 1700–1450 BC).

In its early forms, the Minoan Genius appears hippo-headed or leonine, with a distended stomach like Taweret, an elongated snout reminiscent of a crocodile, donkey ears or wings, and a scaled crocodile tail. By examining the iconography, function, and cultural context of Genii, it becomes clear that Minoan religion absorbed and transformed Egyptian deity motifs into a uniquely Aegean mythological language.

Sir Arthur Evans and Genii

The term Minoan Genius is a modern scholarly designation, not an ancient one. It was coined by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who led the excavations at Knossos Palace. The term refers to a class of supernatural figures depicted in Minoan frescoes, seal stones, and ritual vessels dating roughly from the 18th to 15th centuries BC. These figures often combine the bodies of animals—such as lions, hippopotamuses, or composite beasts—with an upright, human-like posture and behavior.

Minoan Genii are not monstrous or hostile; rather, they appear dignified and purposeful. In the context of natural landscapes and the ewers they carry, Evans described the Genius as “a waterer and promoter of vegetation.”

As Greek archaeologist Nanno Marinatos notes, “Genii are not merely decorative; they participate in ritual action and seem to belong to the sacred sphere” (Marinatos, Minoan Religion, 1993). They are frequently depicted offering libation vessels, pouring liquids, or attending a central goddess figure, indicating their role as divine attendants or ritual agents.

Minoan artists often portrayed Genii standing upright and holding ritual objects such as rhyta (libation vessels). In a notable fresco from the Palace of Knossos, Minoan Genii are shown carrying vessels in a procession-like scene. Their posture and attributes recall depictions of attendants in the iconography of Egyptian deities. As Evans observed, “these daemon-figures show a remarkable affinity to the Egyptian Taweret, adapted to Minoan religious conceptions” (The Palace of Minos, 1921).

Crete-Egypt trade exchange

The resemblance between Minoan Genii and Egyptian deities is no coincidence. Crete maintained active trade relations with Egypt during the Middle and Late Bronze Age. Minoan pottery, seals, and luxury goods have been discovered in Egyptian contexts, while Egyptian scarabs and amulets appear on Crete. In many cases, artistic influence followed these commercial exchanges.

Yet the Minoans did not merely copy Egyptian religious figures—they reinterpreted them through the lens of their own culture. While Taweret is closely associated with childbirth and domestic protection, Minoan Genii often appear in public, ceremonial contexts, frequently linked to palatial ritual and goddess worship.

Functionally, both Egyptian daemon-deities and Minoan Genii serve as intermediaries between gods and humans. In Egypt, protective spirits often stood at thresholds—doorways, beds, tombs—guarding the vulnerable. On Crete, the Genii appear at symbolic thresholds of ritual space, near altars, sacred trees, or goddesses, suggesting that they mediate between the divine and mortal realms. As German scholar Walter Burkert observes, “mythical creatures often serve as guardians of the sacred, marking the boundary between human and divine” (Greek Religion, 1985).

The iconography of the Minoan Genii also reflects Egyptian artistic conventions. Their upright stance, frontal or three-quarter pose, and stylized musculature echo Egyptian formalism more than later Greek naturalism. Yet the Minoans infused these figures with their own aesthetic: fluid movement, dynamic composition, and integration into narrative scenes. This blend of foreign motif and local style demonstrates how religious imagery evolves through cultural contact rather than simple imitation.

It is also significant that Minoan Genii often appear alongside a central female deity, widely interpreted as a goddess of nature or fertility. Their association reinforces their role as attendants or servants of a higher divine power. They do not dominate the scene; they support it. As Marinatos notes, “Genii function as ritual agents who facilitate the epiphany of the goddess.”

Egyptian deity Bes and Minoan Genii

Beyond Taweret, other Egyptian deities and daemon-figures may have influenced Minoan imagery. The Egyptian god Bes, for example, is a dwarf-like protective deity associated with music, dance, and childbirth. Although visually distinct from Minoan Genii, Bes shares certain features—such as female breasts and a protruding stomach—and serves as a benevolent, protective spirit closely involved in everyday human life. This concept of guardian beings likely resonated with Minoan religious sensibilities, which emphasized harmony with nature and the presence of the divine in daily ritual.

Despite these parallels, the Minoan Genii remain uniquely Minoan. They belong to a religious system that differs fundamentally from Egyptian theology. Egyptian religion was heavily textual and hierarchical, with clearly defined gods, myths, and temples. In contrast, Minoan religion is largely reconstructed from art and archaeology, as no written religious texts survive. In this context, Minoan Genii are best understood not as imported Egyptian deities but as hybrid figures—products of cultural dialogue rather than mere imitation.

Their hybrid features reflect the character of the Minoan world: a seafaring civilization at the crossroads of continents. Genii embody that liminal identity, being neither fully animal nor fully human, neither purely Egyptian nor purely Cretan. They stand between categories just as Crete stood between cultures. As Sir Arthur Evans poetically observed, “they are the children of a meeting of seas and beliefs.”

As Evans emphasized, the Minoans did not passively receive Egyptian motifs; they actively reshaped them to fit their own ritual world. In this way, Minoan Genii represent a visual and spiritual dialogue between Crete and Egyptian deities.