A weak zone in Earth’s magnetic field, known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, has expanded at an alarming rate over the past decade, scientists say. Using 11 years of data from the European Space Agency’s Swarm satellite mission, researchers found that the anomaly has grown by an area nearly half the size of continental Europe since 2014.

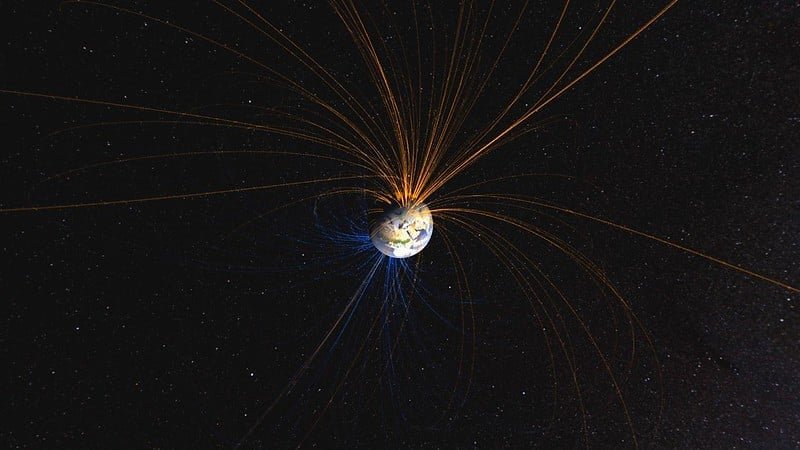

The South Atlantic Anomaly is a region where the planet’s magnetic field is unusually weak, stretching from South America to southern Africa. The magnetic field acts as Earth’s invisible shield, deflecting harmful cosmic rays and charged particles from the Sun.

As this shield weakens, more radiation penetrates the atmosphere, raising concerns for satellites and spacecraft operating above the region.

Uneven weakening raises new scientific concerns

“The South Atlantic Anomaly is not just a single block,” said Chris Finlay, lead author of the new study and Professor of Geomagnetism at the Technical University of Denmark. “It’s changing differently towards Africa than it is near South America. There’s something special happening in this region that is causing the field to weaken in a more intense way.”

The findings, published this month in Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, show that the anomaly expanded steadily between 2014 and 2025. A section of the Atlantic Ocean southwest of Africa has seen an even faster drop in magnetic strength since 2020. This uneven weakening points to complex forces deep within Earth.

Strange magnetic behavior deep beneath the surface

Researchers trace these changes to the planet’s liquid outer core—an ocean of molten iron about 3,000 kilometers beneath the surface.

The movement of this metal generates electrical currents, which produce the magnetic field that surrounds and protects the planet. However, under the South Atlantic, scientists have detected unusual magnetic behavior known as “reverse flux patches,” where field lines loop back into the core instead of flowing outward.

Warning: The South Atlantic Anomaly has expanded by an area nearly half the size of continental Europe since 2014.

—

Using 11 years of magnetic field measurements from the European Space Agency’s Swarm satellite constellation, scientists have discovered that the weak region in… pic.twitter.com/HFJE6jq2Cg

— Brian Roemmele (@BrianRoemmele) October 14, 2025

“Normally we’d expect to see magnetic field lines coming out of the core in the southern hemisphere,” Finlay explained. “But beneath the South Atlantic Anomaly we see unexpected areas where the magnetic field, instead of coming out of the core, goes back into the core. Thanks to the Swarm data we can see one of these areas moving westward over Africa, which contributes to the weakening of the South Atlantic Anomaly in this region.”

Swarm mission delivers unprecedented long-term data

The Swarm mission, launched in 2013 under ESA’s Earth Observation FutureEO program, consists of three identical satellites that measure magnetic signals from Earth’s core, crust, oceans, and atmosphere.

The mission has now produced the longest continuous record of magnetic field data from space, giving scientists a clearer view of how the planet’s magnetic forces evolve.

ESA’s Swarm Mission Manager, Anja Strømme, said the satellites remain in excellent condition. “It’s really wonderful to see the big picture of our dynamic Earth thanks to Swarm’s extended timeseries,” she said. “We can hopefully extend that record beyond 2030, when the solar minimum will allow more unprecedented insights into our planet.”

Risks for satellites and space technology

Scientists say the South Atlantic Anomaly’s ongoing expansion highlights how dynamic—and unpredictable—Earth’s magnetic field can be. While there is no immediate danger to life on the surface, the anomaly poses growing risks for satellites, navigation systems, and other space technologies that depend on the planet’s magnetic protection.