An ancient landmass that once connected parts of India, Madagascar, and the surrounding Indian Ocean islands may have existed millions of years ago, according to new research. The study, led by geoscientist Jothi Jayaraman from the Leibniz Institute for Applied Geophysics, revives the long-dismissed idea that a lost continent of Lemuria once stretched across the Indian Ocean.

The findings, published on ResearchGate, focus on microscopic mineral grains called zircons found in volcanic rocks on the island of Mauritius. While the island is relatively young in geological terms, uranium-lead dating reveals that some of the zircon crystals are more than three billion years old, far older than the island itself.

That age suggests they came from much older continental crust, possibly from a submerged continent that researchers now call “Mauritia.”

Zircon crystals offer clues to Earth’s deep past

Zircons serve as reliable geological timekeepers. Once embedded in rock, their isotopic composition remains stable for billions of years. Jayaraman and his team compared the ancient zircon grains from Mauritius with similar rocks that were found in India and Madagascar.

The close match points to a shared geological history, indicating that these regions may once have been part of the same landmass before tectonic shifts pulled them apart.

The study also draws on seismic and gravity data from beneath the Mascarene Plateau, a submerged region northeast of Madagascar. The data show that the crust in this area is up to 30 kilometers (about 18.6 miles) thick, much deeper than the normal ocean floor.

That unusual thickness supports the idea that the plateau may be part of a sunken continental fragment now buried under lava flows and ocean sediments.

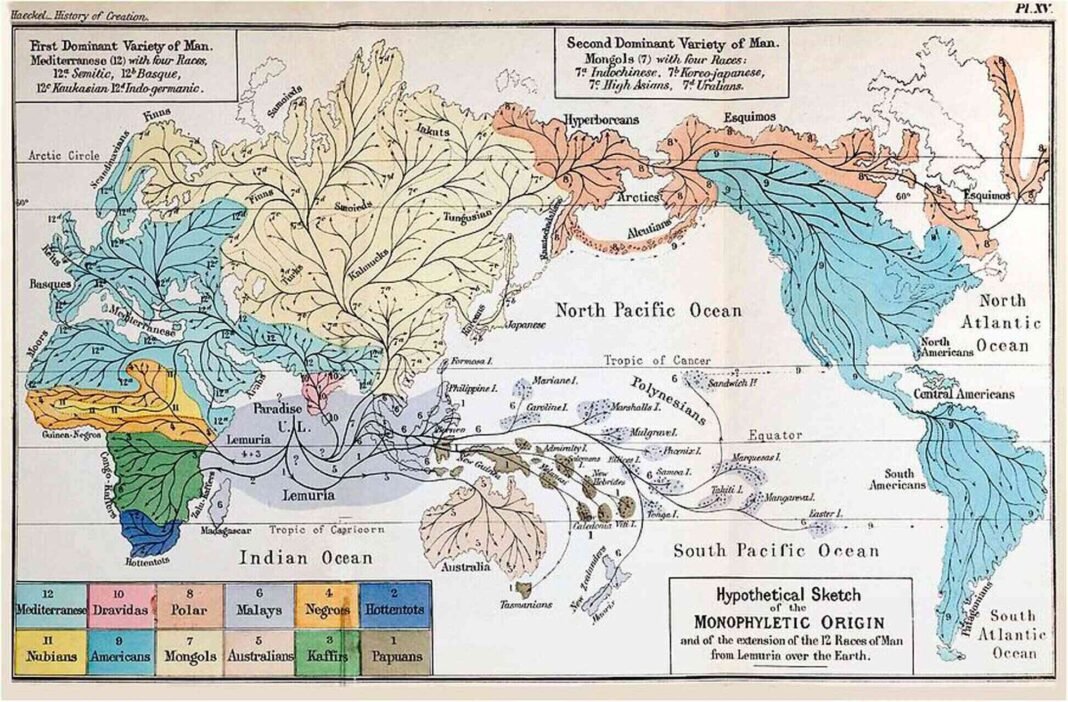

Though the idea of a lost continent in the Indian Ocean dates back to the 19th century, it was largely rejected by modern science.

Modern data renews interest in Victorian-era theory

In 1894, British zoologist Philip Sclater proposed the existence of “Lemuria” to explain why lemurs were found in both India and Madagascar but not in mainland Africa. Lacking today’s technology, Sclater’s theory was dismissed after the rise of plate tectonics in the mid-20th century.

Jayaraman’s study revives the discussion, this time backed by modern dating techniques and deep-earth imaging. While some experts remain skeptical—arguing that microcontinents often form as scattered fragments rather than a single body of land—the scale of Mauritia’s inferred size has reignited interest. If accurate, it could have once covered an area comparable to Greenland.

The study also points to broader implications. Mapping these hidden land pieces could improve scientific models of how Earth’s supercontinents formed and broke apart. It may also offer clues about ancient climate systems and ocean currents.

Jayaraman writes that future deep-sea drilling across the Mascarene Plateau could reveal whether the remains of this ancient continent still lie entombed below. For now, the debate over whether the lost continent of Lemuria truly existed continues, bridging Victorian speculation and modern geophysics.